“I feel like it’s an artist’s responsibility to interpret reality. History is not static, and archive is not static. They evolve as we evolve and gain new perspective. And they are always translated. Why not by an artist?”

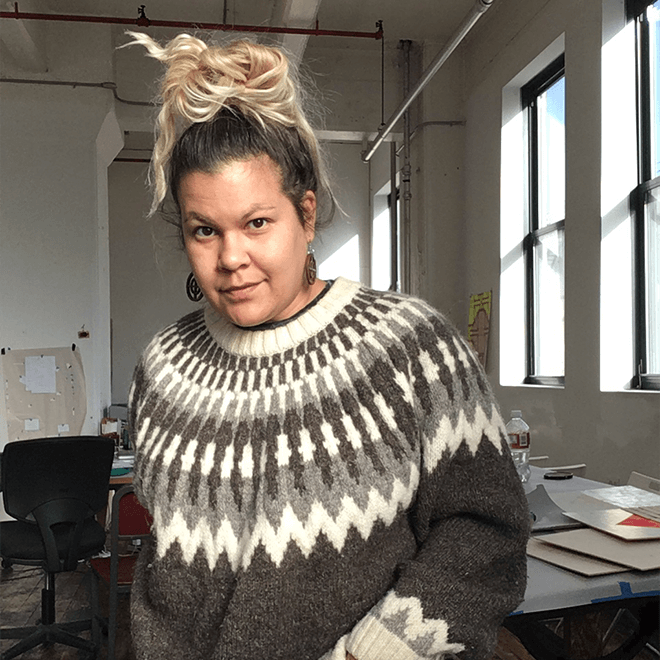

Heather Hart, assistant professor in the Department of Art & Design, is an interdisciplinary artist exploring power in thresholds, questioning dominant narratives and creating alternatives to them through architectures and viewer activation. Her topics of expertise include Wikipedia/wiki in the classroom; public art, participatory art, space + built environment and art by African American artists; digital archives of oral history; and artists as nonprofit founders.

What is your research all about and why is it important?

I am a sculptor. I started as the daughter of two artists, thinking about the differences between the oral histories that I was hearing from my folks and grandparents and family members and elders, versus the histories that were documented in the archives and historical records. They overlapped, but they never matched perfectly. So I’m always thinking about my work akin to the archive, and space, as transmutable, something that is interpreted and may be claimed by the public. I play around with themes of liminality and interpretation, history and future.

Take a rooftop or a porch; these things are normally in between other spaces. We move through them. I pull those thresholds out of the architectural space—out of the built environment—and place them out of context and independently. This helps us identify their power, but also to think about how we naturally interact with them. Liminal spaces are often overlooked, and I see them as a prompt for possibility, for shifting narrative and pivoting authorship. A reclamation. Interacting with these sculptures can trigger a somatic response that carries nostalgia or fantasy as well as implications for the epigenetic inheritance, which fascinates me. It’s satisfying to know that there is science published on this (see research by Dr. Brian Dias), because those of us with ancestral trauma know instinctively how trauma re-emerges in future generations.

Recently I have been exploring what “Black space” is, with the idea of creating architectural “quotes,” thinking about this threshold space. But I found that a disproportionate space in the archives that I researched to find these spaces were full of Black trauma, and was missing so much of what Black life means to me. While the archive is important, there are so many other spaces that are undocumented or under-documented, and so I started thinking about what those spaces of joy might be in order to interrupt the existing archive. I began looking for Black space in music, film, books and oral histories to fill in gaps. Where were they sitting in these sources? What were their environments like? What were the objects and spaces that may be overlooked between the events and the facts that were happening in those records? I started pulling things out, thinking about the idea of Black fantasy. And then I started making these 3D models fragmenting these spaces. Some of the models were recognizable, and some were very obscure and abstract. My research led me to suggest a relationship and communication between all the objects I was collecting and creating—a space between them. I recreated Tommie Smith’s and John Carlos’s 1968 Olympic podium and the staircase that the Nicholas brothers danced on in the movie Stormy Weather. Putting them together, they are entirely random and divergent stories, but there are similarities among these forms, and also a shared history connecting them. That is what I’m most interested in; can I point to the space between?

What does arts-based research mean to you?

I think the arts are similar to other fields in many ways. We go into an archive. We do a lot of reading. But I think it’s in the nature of being an artist to be imaginative, to be open and to interpret. James Baldwin said the artist has “the responsibility to reveal all that he can discover.” We are charged with finding ways to reveal and give space to everything in our reality and fantasy. I feel like it’s an artist’s responsibility to interpret reality. History is not static, and archive is not static. They evolve as we evolve and gain new perspective. And they are always translated. Why not by an artist?

How does your work as an artist affect your teaching?

I needed to have a significant amount of experience under my belt before I felt ready to profess anything. I try to help my students think about spaces of disruption and possibility, to be audacious and generous. I help my students fantasize about meaning. I ask them to dig deep to find what makes their authorship unique and weird and wild. That’s all the stuff that I try to do in the studio.

Can you tell us about the Black Lunch Tables?

Sure—that is a project that I started pretty early on. I was at an art residency, and I met a collaborator, jina valentine, in 2005. We were kind tricksters—and we did a few projects that were designed with that in mind. One of those was segregating the lunchroom. We had some pushback from some of our white friends about how disruptive and subversive it was. They asked why we needed to do that in a space that was otherwise really idyllic. But, for us, it was a kind of space we found everywhere else in the world, and it happened to point to the fact that they didn’t think about this in their normal lives. This situation/space opened up a space of dialogue with them that, for me, wasn’t repeated in public until the George Floyd murder. And amongst those seated at the table the dialogue explored: What does a “safe space” mean? Should I exhibit my work in February? Do I have a civic responsibility in my artwork? Things like that. After that residency, jina and I began hosting workshops and house parties, and perpetuating that space of dialogue. It snowballed into an ongoing project we called Black Lunch Table, a discursive space that archives discussions and hosts them on a searchable site, thinking about filling gaps in historical records and self-authorship.

In 2019 we became a nonprofit. The program has been nomadic; we’ve been to South Africa and Canada and Trinidad and Tobago. Now we have a new executive director and a board, which is really exciting. It’s another way that my work encompasses reparative practices.